Circa 1748

Early Provenance of the Commodes

It is likely that these commodes were originally intended for Madame de Mailly as part of a commission by the King for her apartment at the Château de Choisy. On 30th October 1742, a single blue and white commode was delivered followed by a blue and white encoignure on January 29th 1743. Both of these pieces are now in the Louvre Museum in Paris. The second part of his order for her Salon was abruptly cancelled as a result of her fall from grace as the mistress of the King. Two of her sisters followed in succession, the Marquise de Vintimille, who died giving birth to the King’s son, the Comte de Luc. M de Mailly returned to look after the baby but was quickly supplanted by another sister, the Duchesse de Châteauroux. She too died young in December 1744. The King was heartbroken but found the usual intrigues of his aristocratic mistresses in seeking wealth and power tiresome. It was assumed that he would take on the fourth sister, Madame de Lauragais. While he liked her company, it was not to be and nor would he go back to M. de Mailly. The King’s mistresses had always been drawn from noble families; a bourgoise was unthinkable, nor could she be formally presented to the King and Queen.

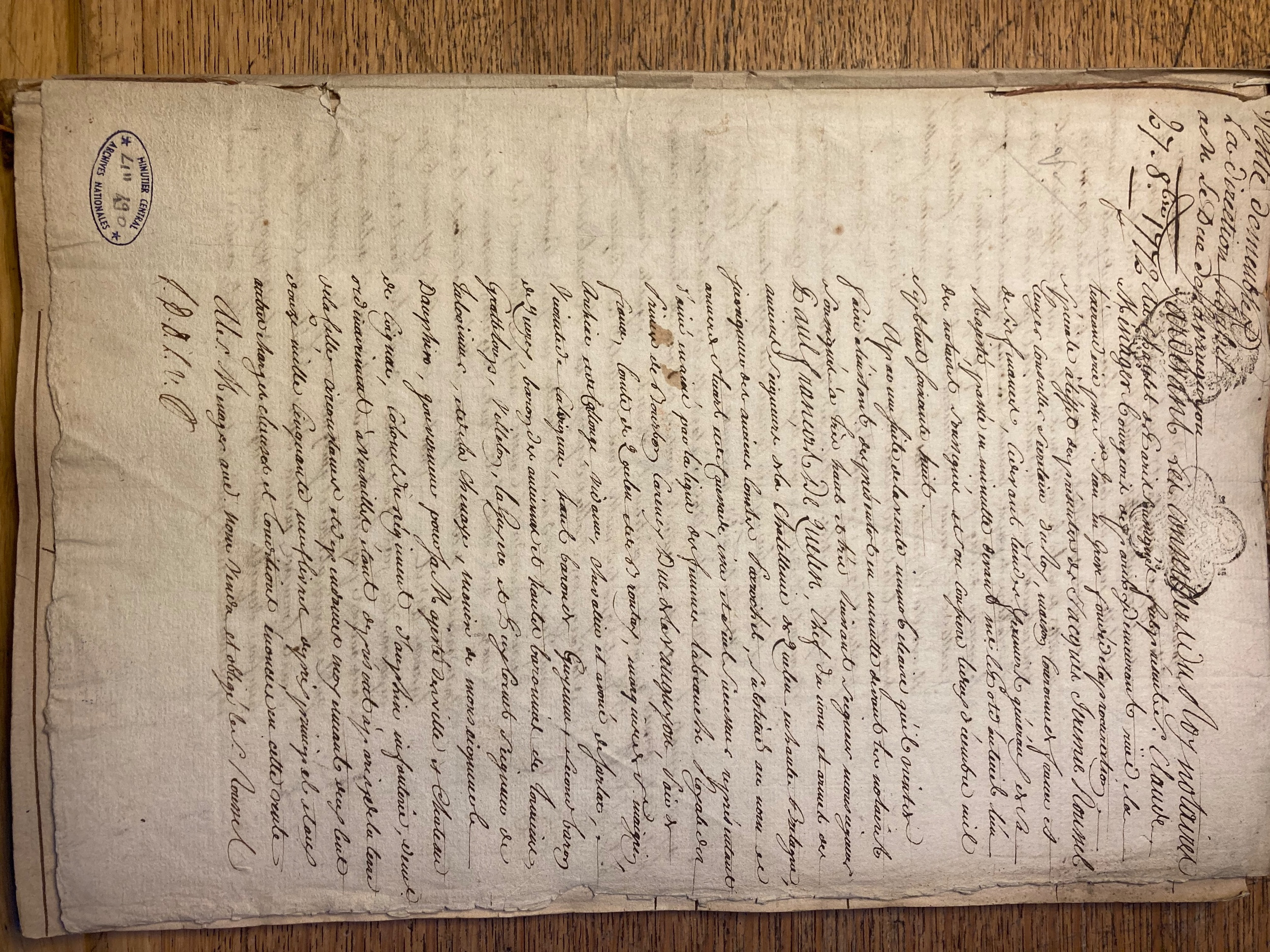

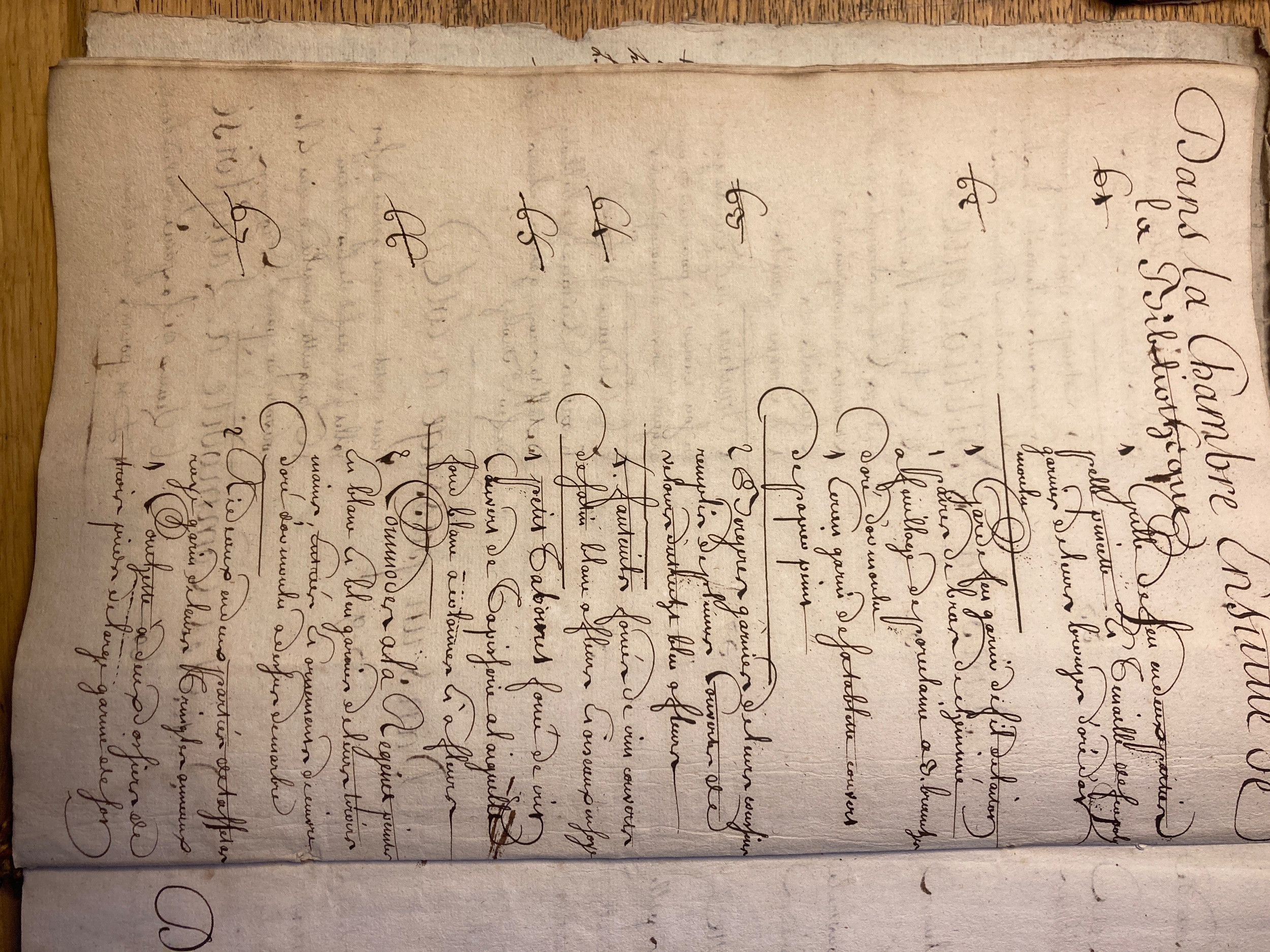

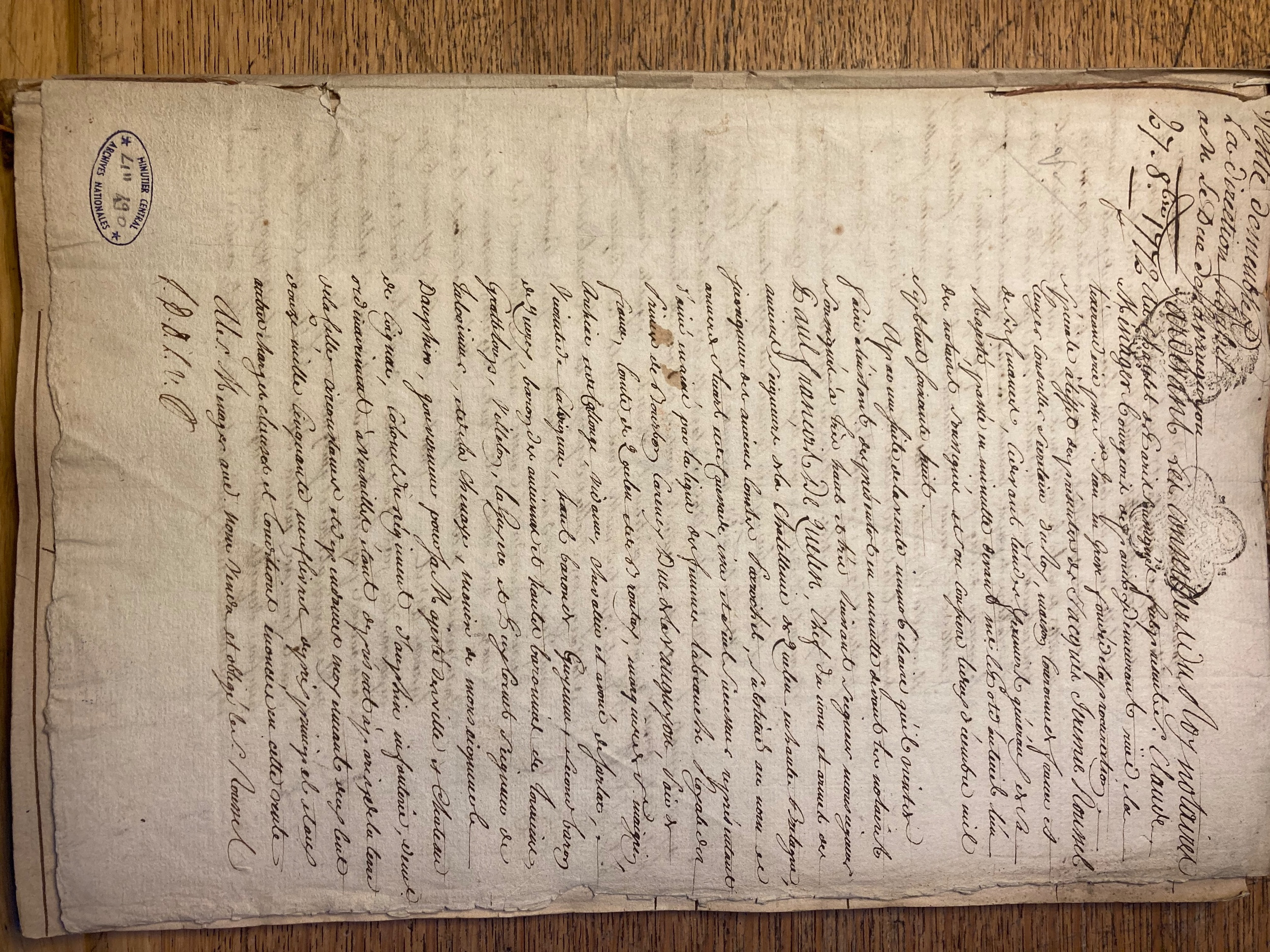

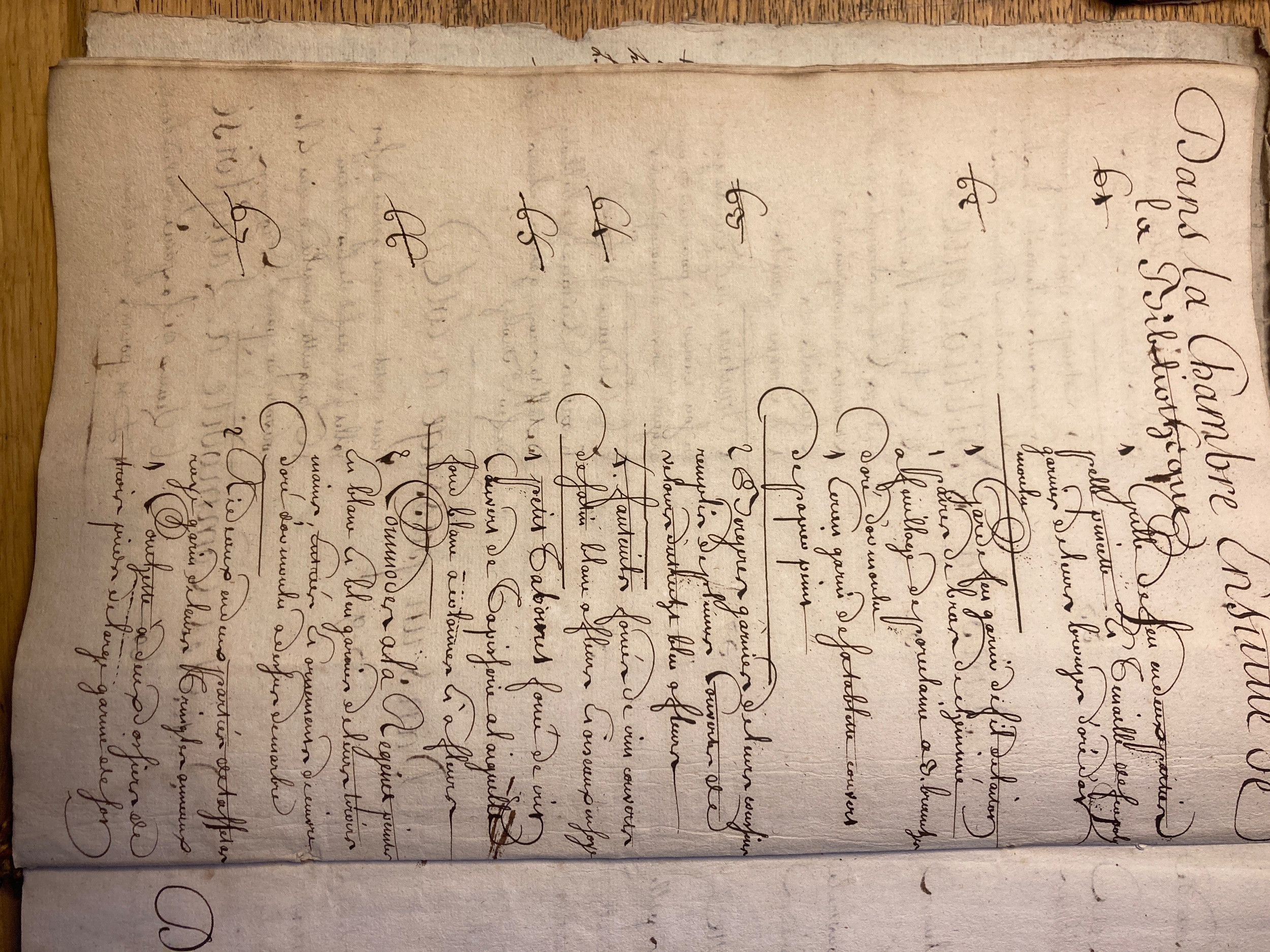

In February of 1745, to celebrate the marriage of the Dauphin a whole series of masked balls was organised. One of these took place in the King’s riding school at Versailles, which was where the King probably met Madame de Pompadour for the first time. The King thus knew her by sight from 1742 as she had caught his attention in 1744 by driving her phaeton in front of him while the King was hunting in the forest of Senart. The attraction was instant and although hesitant at first to install her as his mistress, she was quickly given the second-floor apartment of the late Duchesse de Châteauroux at Versailles and given the title of Marquise of Pompadour. When Madame de Pompadour became Mistress in 1745, she had to rapidly furnish her apartment on the second floor of the Château de Versailles. The commodes must have already been ordered by the King but not delivered as they have to date before April of 1745, because the bronzes do not bear the crowned C mark. This somewhat unworkable tax on all metal objects, including pieces in for repairs, was passed by an edict of the Parlement in March of 1745; it was revoked in February 1749. This means that the Marquise had to have bought them from Hébert before April 1745; although it took a month or so actually to implement the edict practically. In 1748 she re-decorated the apartment and split into two the very large room that the commodes had probably been living in. This was the same year that she bought the Château de la Celle and the commodes were sent there. She immediately renamed it the Château de la Celle de Saint-Cloud in honour of the Merovingian Prince priest saint who had founded his monastery on a height overlooking the Seine in the 6th. Century. It has been called that ever since. She added only a small wing to the left of the Cour d’Honneur. Some interiors remain to this day, but the Salon Bleu contains only one mirrored boiserie in the rococo manner and is described in the 1975 Monuments Historiques dossier as originally blue and white. The commodes (number 66) are described in the 1772 Inventory of the house for the Duc de la Vauguyon . This inventory was drawn up on the death of Roussel to recoup some of the enormous debt that was owed to Vauguyon, the house and its contents were passed to him.

Provenance of the Chateau de la Celle de Saint Cloud

Madame de Pompadour: (1721-1764)

Having bought the Chateau in 1748 she sells it to Roussel in 1751.

Jacques-Jérémie Roussel de Rocquencourt (1712-1776).

She was well known to him as he was one of the first investors in the Sèvres porcelain factory. The Chateau and its contents appear to be accepted by the Duc de la Vauguyon to settle Roussel’s debts with him as the 1772 Inventory indicates that it was sold on the death of the next owner.

1st Duc de la Vauguyon (1706 -1772)

He was from a very old aristocratic family and close to Louis XV, who was born in 1710. He was appointed menin, that is, in charge of the education of the Dauphin which was an exceptionally important role as it required the complete confidence of the King.

2nd Duc de la Vauguyon (1746 - 1828)

The 2nd. Duke inherited the chateau from his father and sold it in 1775 to:

Louis Pierre Parat de Chalandray (1746-1836)

He is very fortunate to survive the Revolution but does so because of his progressive views on education. This preserves his estate intact and the contents of his houses. Anyone who was perceived to have emigrated, even those who sent their children to safety, was classed as an Émigré. While his wife remained in plain sight in Paris, he, on the other hand, hid himself at La Celle, protected by his gardener at considerable risk. Both, had they been caught, would have been guillotined.

However, although he received his estate, Château and its contents back, many of his papers remain in the Convention papers seized at the Revolution. In 1804 he sold it to:

Vicomte Charles Gilbert Morel de Vindé (1759-1842)

The Château, still containing the commodes, passes to his son and heir who sells the Château de la Celle to Jean-Pierre Pescatore; but the commodes pass to his heirs. In 1800 his son’s daughter, Cecile Marie de Morel-Vindé married Hyppolyte Terray (1774-1849) and their son,

Charles Louis Terray de Vindé (1846-1880)

He inherits the Château de la Motte Tilly in 1839. It is probably at this point that the commodes make their way to this new home. His unfortunate grandfather, Jean Terray, Vicomte de Rosières makes the fatal mistake of sending his four children to safety in England. He and his wife remain in France, hoping to avoid confiscation but the revolutionary government of France during the Revolution adjudges them as Émigrés anyway and they are guillotined in 1794. All their property is seized so that when their son returned in 1797, he found his father’s Château completely stripped of its contents. Contemporary photographs in the Monuments Historiques show the house furnished with heavy 19th. Century furniture completely unsuited to the elegant 18th. Century interiors still intact. Charles Louis’s second daughter, Anne Terray de Morel-Vindé (1846-1880) then married Guy de Rohan-Chabot, Comte de Chabot. Her elder sister married the Comte de Narcillac in 1861. However, the Narcillac heirs, having inherited the Château, decide to sell it, complete with the commodes, to their cousin:

Charles-Gérard de Rohan-Chabot, Comte de Chabot (1870-1964).

He begins to refurnish the Château with more suitable furniture and then with his daughter:

Aliette, Marquise de Maillé (1896-1972)

She suffered the tragic loss of her brother, Gilbert, and her husband within 11 days of each other in the 1st World War in 1918. Her daughter, born posthumously, died of cancer in 1970. There were no heirs and the commodes, by now, were in her apartment at the Rue Colonel-Combes. She gave the Château de la Motte-Tilly to the French state with a substantial endowment so long as it remained open to the public but not lived in. She was one of France’s leading Medieval archaeologists and scholars.

| DIMENSIONS | CM | INCHES |

|---|---|---|

| Width: | 158 | 62.1/4 |

| Depth: |

68 |

26 3/4 |

| Height: | 91m | 35 3/4 |